When it comes to controlling prescription drug spending, Medicaid generic drugs are the quiet heroes of state health budgets. Even though they make up 84.7% of all Medicaid prescriptions, they only account for 15.9% of total drug spending. That’s not an accident. States have spent years building systems to make sure these low-cost medications stay affordable - without cutting off access for the millions who rely on them.

How Medicaid Gets Its Generic Drug Discounts

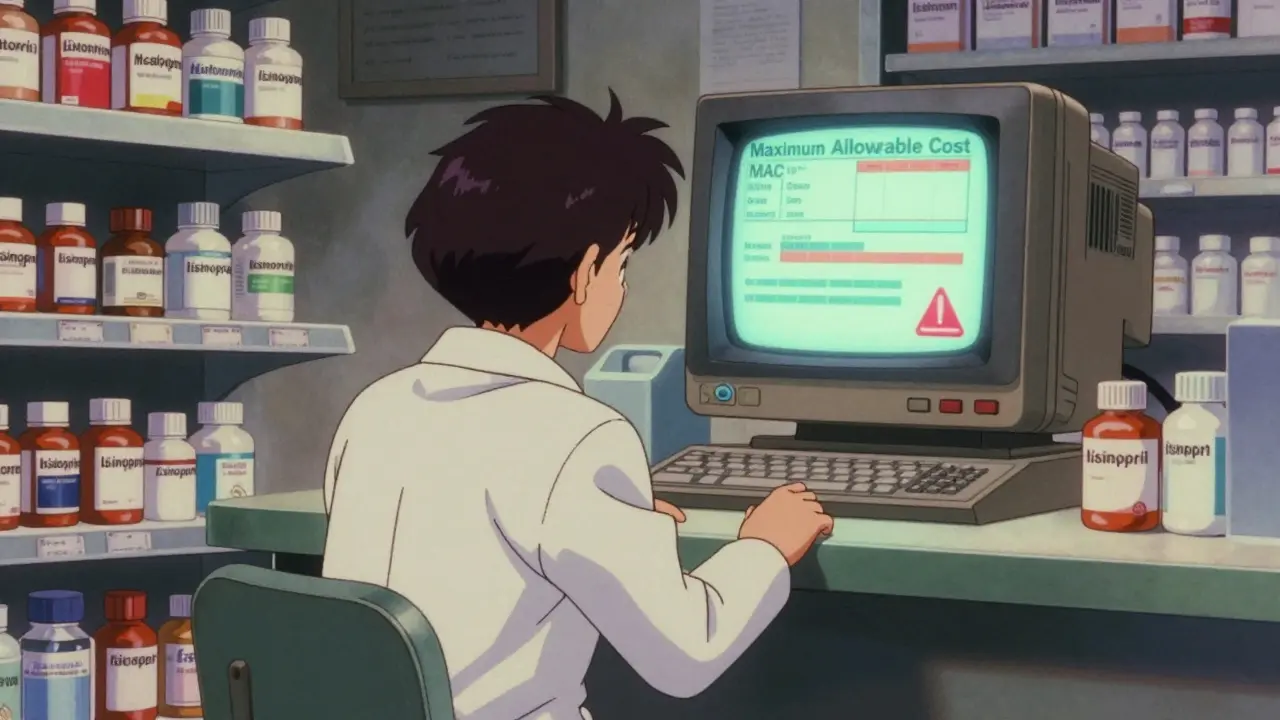

The foundation of all this cost control is the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), created by federal law in 1990. Under this program, drug manufacturers must give states rebates on every generic drug sold to Medicaid. For generics, that rebate is at least 13% of the average manufacturer price - or the difference between that price and the best price the company offers anywhere else, whichever is higher. It’s a simple formula, but it works. Without MDRP, Medicaid would be paying far more for everyday medications like metformin, lisinopril, or amoxicillin. States don’t get to negotiate extra rebates on generics like they can with brand-name drugs. That’s a big limitation. But they’ve found other ways to squeeze out savings without breaking federal rules.Maximum Allowable Cost Lists: The Most Common Tool

Forty-two states use Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists to cap how much they’ll pay for a generic drug. Think of it like a price ceiling. If a pharmacy tries to bill Medicaid for a generic pill at $5, but the state’s MAC is $3.25, the state only pays $3.25. The pharmacy eats the rest - or finds a cheaper supplier. These lists aren’t static. Thirty-one states update them quarterly or more often, adjusting for price drops in the open market. But here’s the catch: 68% of states update MAC lists monthly or less. That means if a generic drug suddenly drops to $2.50, but the state’s list still says $3.50, pharmacies get paid too much - and taxpayers foot the bill. Worse, if the price spikes and the MAC isn’t updated fast enough, pharmacies might refuse to fill the prescription because they’d lose money. Independent pharmacies report this is a real problem. A survey of 1,200 community pharmacies in late 2024 found that 74% had seen claims denied or payments delayed because their state’s MAC list didn’t match what they paid for the drug. That’s not just a billing glitch - it’s a barrier to care.Forcing Generic Substitution

Forty-nine states require pharmacists to substitute a generic version whenever it’s available and approved by the doctor. That’s not just policy - it’s law. If a prescription says "Lisinopril," and a generic version exists, the pharmacist must give the generic unless the doctor specifically writes "dispense as written." This isn’t just about savings. It’s about consistency. Patients get the same medication, just at a fraction of the cost. And because generics are bioequivalent to brand-name drugs, there’s no clinical downside. This policy alone saves states billions each year.

Therapeutic Interchange and Preferred Drug Lists

Twenty-eight states go further. They create Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs) - essentially, a curated list of generics that Medicaid will cover without extra paperwork. If a doctor wants to prescribe a non-preferred generic, they often need prior authorization. That’s not a ban - it’s a nudge. Some states even use therapeutic interchange. That means if a patient is on a more expensive generic, the pharmacist can switch them to a cheaper one in the same drug class - say, switching from one brand of metformin to another - without calling the doctor. This works because the drugs are medically equivalent, but the price difference can be huge.Going After Price Gouging

Some states aren’t waiting for market forces. They’re passing laws to stop manufacturers from jacking up prices on old, off-patent drugs. Maryland’s 2020 law is one of the first and most aggressive. It allows the state to fine drugmakers if they raise prices on generic drugs without new clinical evidence - like suddenly doubling the cost of a 60-year-old antibiotic. Other states, including California and Colorado, have followed suit. These laws don’t target every price increase - just the ones that look like exploitation. Critics say this interferes with free markets. But states argue that when a drug has no competition - say, one company controls 90% of the supply - then it’s not a market anymore. It’s a monopoly.Managing the Supply Chain

Here’s the dirty secret: even with all these savings tools, generic drugs are still in short supply. In 2023, 23 states reported shortages of critical generic medications. The average shortage lasted nearly five months. Why? Because many generics are made overseas, and production can be disrupted by everything from natural disasters to factory inspections. Three companies now control 65% of the generic injectable market - meaning if one factory shuts down, dozens of drugs vanish. Twelve states introduced new laws in 2024 to fix this. Some are stockpiling essential generics. Others are creating backup suppliers or partnering with other states to buy in bulk. Oregon and Washington lead a multi-state purchasing pool that negotiates supplemental rebates on 47 high-volume generics - something no single state could do alone.

Who’s Really Controlling the Prices?

Here’s a twist: most states don’t buy drugs directly. They hire Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) like OptumRx or Magellan to handle prescriptions. PBMs are middlemen. They negotiate with manufacturers, set reimbursement rates, and process claims. But they don’t always pass savings along. In 2024, 27 states passed new rules requiring PBMs to disclose what they actually pay for generic drugs. Nineteen of them now require transparency on acquisition costs. Why? Because some PBMs were keeping the difference between what they paid and what they reimbursed pharmacies - a practice called spread pricing. When states started cracking down, pharmacy owners cheered. Patients noticed fewer denials. But PBMs pushed back hard, arguing these rules hurt their ability to negotiate discounts.The Big Trade-Off: Savings vs. Access

Every cost-saving strategy has a flip side. MAC lists that are too low can lead to drug shortages. Price caps that are too tight can make manufacturers quit the market. A 2024 Congressional Budget Office report warned that overly aggressive state pricing could reduce generic availability - and push patients toward more expensive brand-name drugs or hospital visits. The goal isn’t to slash prices at all costs. It’s to keep the system balanced. Medicaid needs to pay enough so manufacturers don’t abandon the market, but not so much that it drains state budgets. That’s why experts like Dr. Mark Duggan from Stanford say reforming the MDRP rebate formula for generics could unlock billions in savings - especially during drug shortages. If manufacturers had to pay higher rebates when supply is tight, they’d have more incentive to keep producing.What’s Next?

By 2026, 22 states plan to have strategic stockpiles of critical generics. Fifteen more are expected to introduce legislation targeting generic pricing in 2025. The federal government is stepping back - CMS canceled its own drug pricing model in March 2025, leaving states as the main drivers of change. The rise of GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy is adding pressure. These are brand-name drugs, but they’re being prescribed for obesity - a condition many Medicaid patients have. Thirteen states already cover them, but only with strict prior authorizations. If federal rules force all Medicaid programs to cover them, states could face an extra $1.2 billion in annual costs. That’s why the focus on generics is only getting stronger. They’re the foundation. When they work, the whole system works.How do Medicaid generic drug policies save money?

Medicaid saves money by requiring drug manufacturers to pay rebates under the federal Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, using Maximum Allowable Cost lists to cap reimbursement, mandating generic substitution, and enforcing therapeutic interchange. These strategies ensure that 84.7% of prescriptions are filled with generics, which cost far less than brand-name drugs.

Why don’t all states have the same generic drug policies?

Each state designs its Medicaid program within federal guidelines, so policies vary based on budget pressures, political priorities, and pharmacy market conditions. States with higher drug spending or more generic shortages tend to have stricter controls, like price gouging laws or frequent MAC list updates.

Can state price controls cause generic drug shortages?

Yes, if price caps are set too low, manufacturers may stop producing a drug because it’s no longer profitable. The Congressional Budget Office warns that aggressive state pricing could reduce availability, forcing patients to use more expensive alternatives and increasing overall Medicaid costs.

What’s the role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) in Medicaid generic drug costs?

PBMs act as middlemen between states and pharmacies, negotiating prices and processing claims. Some PBMs kept profits by charging Medicaid more than they paid for drugs (spread pricing). In 2024, 27 states passed laws requiring PBMs to disclose their actual acquisition costs to prevent this practice.

Are generic drugs as safe and effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and bioequivalence as their brand-name counterparts. The only differences are in inactive ingredients or packaging - which don’t affect safety or effectiveness.

Which states are leading in generic drug cost control?

Maryland, Oregon, Texas, California, and Colorado are among the leaders. Maryland has price gouging laws, Oregon and Washington run a multi-state purchasing pool, Texas uses gene therapy carve-outs and MAC lists, and California and Colorado have Prescription Drug Affordability Boards that set spending caps.

How often do states update their Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists?

Thirty-one states update MAC lists quarterly or more often, but 68% update them monthly or less. This lag can cause problems - if generic prices drop, pharmacies may lose money; if prices rise, patients may face delays or denials.

What’s the impact of generic drug consolidation on Medicaid?

Three companies now control 65% of the generic injectables market. This lack of competition makes it easier for prices to spike and harder to find alternatives during shortages. States are responding by diversifying suppliers and building strategic stockpiles.

Roshan Joy

January 11, 2026 AT 03:55Wow, this is actually super helpful 🙌 I never realized how much work goes into keeping generics affordable. The MAC lists thing is wild - imagine your pharmacy losing money just because some bureaucrat forgot to update a spreadsheet. 😅

Adewumi Gbotemi

January 12, 2026 AT 04:54Here in Nigeria, we wish we had this system. Generic drugs are expensive too, but no one is trying to control prices. Just hope one day we get smart like this.

Michael Patterson

January 13, 2026 AT 00:29Okay so let me get this straight - states are capping prices on life-saving meds because they’re ‘too expensive’? And then they wonder why pharmacies can’t stay open? I mean, come on. This isn’t socialism, it’s just bad economics. You can’t tell a company they can only make 10 cents on a pill that cost $3 to produce and expect them to keep making it. The CBO was right - this is gonna backfire hard. I’ve seen this movie before. It ends with people driving 3 hours to get their insulin because the local pharmacy closed. 🤦♂️

Matthew Miller

January 14, 2026 AT 19:15Let’s be real - this whole system is a joke. PBMs are the real villains here. They’re the ones pocketing the difference between what they pay and what they reimburse. States are just playing whack-a-mole while the real crooks laugh all the way to the bank. And don’t even get me started on how these ‘therapeutic interchange’ policies are just thinly veiled rationing. You think patients want their metformin swapped out like a baseball card? No. They want consistency. And if you cap prices too low, you get shortages - which means more ER visits. Which means MORE spending. Brilliant.

Madhav Malhotra

January 15, 2026 AT 02:19As someone from India, I can say this is kinda similar to how our public health system works - but without the fancy tech or data. We rely on generics too, and yeah, sometimes the supply chain breaks. But I’m impressed how U.S. states are trying to fix it with smart policy. Maybe we can learn something here.

Priya Patel

January 17, 2026 AT 01:21OMG I didn’t even know about MAC lists!! I thought generics were just cheaper because they’re ‘generic’ but turns out it’s like a whole secret economy of price caps and pharmacy drama 😱 I’m so glad someone’s fighting for this stuff. Also, PBMs are the worst. I’ve had my prescriptions denied for NO REASON. Like, I’m on Medicaid and I still get treated like I’m scamming the system. 😤

Jason Shriner

January 17, 2026 AT 22:03So let me get this straight - we’re saving billions by forcing people to take the cheapest version of a drug... but if that version isn’t available, they go without? And the solution is... more bureaucracy? Wow. Truly, we’ve reached peak American healthcare. The only thing more ironic than this system is the fact that we call it ‘affordable care.’

Alfred Schmidt

January 19, 2026 AT 20:11STOP. STOP. STOP. The fact that you’re even praising this system is horrifying. You think MAC lists are ‘smart’? They’re a death sentence for small pharmacies. You think PBMs are ‘cracked down on’? They just moved the fraud elsewhere. And don’t even mention ‘therapeutic interchange’ - that’s just medical gaslighting. Patients aren’t widgets. You don’t swap their meds like a battery. This isn’t policy - it’s cruelty dressed up as fiscal responsibility. I’ve seen people cry because their doctor couldn’t get them their usual generic. Don’t you dare call this ‘savings.’ It’s exploitation.

Vincent Clarizio

January 20, 2026 AT 12:30Look, I get the math - 84% of prescriptions, 16% of cost - sounds like a win. But here’s the philosophical problem: when you turn healthcare into a spreadsheet, you lose sight of the human. Who decides what ‘affordable’ means? Is it the state auditor? The PBM analyst? The manufacturer’s CFO? No one’s asking the patient. And when the MAC list is outdated, it’s not a ‘billing glitch’ - it’s a denial of care. We’re not just managing costs; we’re managing desperation. And that’s not a policy. That’s a moral failure. The real question isn’t ‘how do we save money?’ It’s ‘how do we not break people in the process?’

Sam Davies

January 21, 2026 AT 09:53Oh, how quaint. America, the land of innovation, now reduced to haggling over the price of metformin like it’s a flea market. The fact that we need 27 state laws to stop PBMs from pocketing the difference between what they pay and what they charge is less ‘policy’ and more ‘national embarrassment.’ Honestly, I’d rather just have a single-payer system and be done with this circus.

Christian Basel

January 22, 2026 AT 02:39MAC lists, PDLs, therapeutic interchange - all classic cost-containment levers. But the real issue is structural: vertical integration of PBMs with insurers and pharmacy chains creates perverse incentives. The lack of price transparency in the supply chain is a classic information asymmetry problem. Without regulatory intervention, market failure is inevitable. The CBO’s warning about reduced availability is a textbook externality - negative supply-side shock from price ceilings. We need dynamic pricing models aligned with marginal cost, not static caps.

Alex Smith

January 23, 2026 AT 15:45Okay, but why are we still letting three companies control 65% of injectables? That’s not a market - that’s a cartel. And we’re surprised when prices spike? We need to break up these monopolies, not just cap prices. Also - why is Oregon and Washington doing this multi-state thing and no one else is? Lazy. Or scared. Or both.

Jennifer Littler

January 24, 2026 AT 04:05As someone who works in Medicaid admin, I can tell you - the MAC list delays are a nightmare. We update quarterly, but the market moves weekly. Pharmacies call us crying. Patients show up at clinics with empty bags. We’re not villains - we’re stuck between a rock and a hard place. But I agree: we need real-time pricing feeds. It’s 2025. We have the tech. Why are we still using Excel?

Sean Feng

January 25, 2026 AT 00:24Generics work. Stop overcomplicating it. Let the market do its thing. If a drug is too cheap to make, stop making it. People will use the brand. If the brand is too expensive, the state can pay for it. Simple.