When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you might not realize that behind the scenes, a detailed science-based system is deciding whether the pill in your hand is a safe swap for the brand-name version your doctor wrote. This system is called therapeutic equivalence, and it’s managed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) through a tool called the Orange Book. It’s not just bureaucracy-it’s what lets pharmacists confidently hand you a cheaper generic instead of the brand, without asking your doctor again. But not all generics are treated the same. Some carry a green light. Others? They come with warning labels. Understanding how these codes work can help you make smarter choices about your meds.

What the FDA Means by "Therapeutic Equivalence"

Therapeutic equivalence doesn’t mean two drugs are identical. It means they’re close enough in how they work inside your body that switching between them won’t change your health outcome. The FDA says it clearly: a substituted drug must produce the "same clinical effect and safety profile" as the original when taken under the same conditions. That’s a high bar. It’s not enough for two pills to have the same active ingredient. They need to release that ingredient at the same rate, absorb the same amount into your bloodstream, and deliver the same result in real patients.

This system was created in 1980, after Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act. The goal? Lower drug costs without risking patient safety. Before this, many doctors and pharmacists were hesitant to switch patients to generics-no one knew if they’d work the same. The Orange Book changed that. It became the official, science-backed reference for which generics are interchangeable. Today, over 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generics, and this system is why.

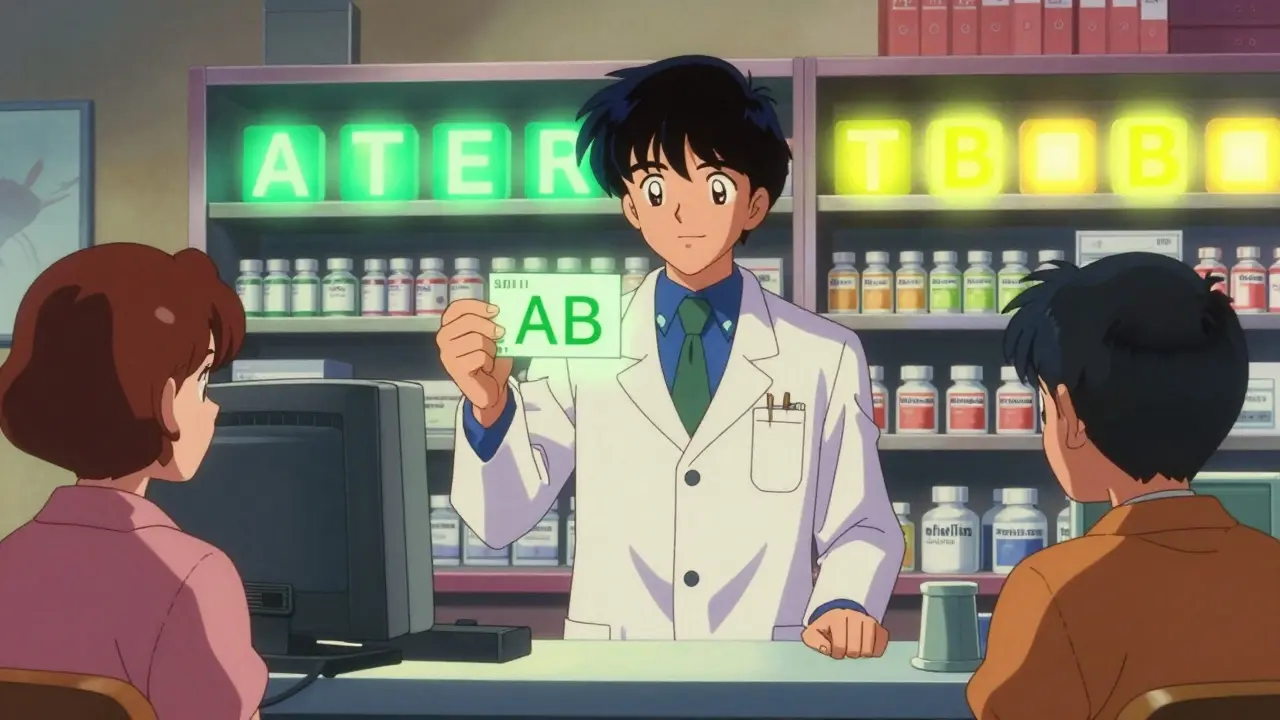

The Letter Codes: What A, B, and Their Subtypes Mean

The FDA doesn’t use complicated jargon. It uses simple letters. The first letter tells you everything you need to know.

- A means the generic is approved for substitution. You can swap it without asking your doctor.

- B means the FDA doesn’t yet have enough evidence to say it’s interchangeable. It might be safe, but it needs more study.

But it gets more detailed. After the first letter, you’ll often see numbers or extra letters. For example:

- AB is the most common. It means the generic passed bioequivalence testing-its absorption in the body matches the brand.

- AB1, AB2, AB3 appear when multiple brand drugs exist for the same condition. Each number points to a different reference drug. You can only swap within the same group.

- BC means it’s an extended-release product with unclear bioequivalence. These are tricky because how the drug releases over time matters.

- BT is for topical creams or ointments where skin absorption is hard to measure.

- BN covers inhalers and nebulizers. Getting the right dose from a puff or mist isn’t as simple as swallowing a pill.

- BX is a red flag. There’s not enough data to even guess if it’s equivalent.

These codes aren’t random. They’re based on real data: how fast the drug enters your blood, how long it stays, and whether it works the same in clinical studies. The FDA tests this using blood samples from healthy volunteers. If the generic’s drug levels fall within 80%-125% of the brand’s, it passes.

Why Some Generics Get a "B" Rating-Even When They Should Work

It’s frustrating, but true: some generics with a "B" rating might be perfectly safe and effective. The problem isn’t always the drug-it’s the test.

For simple pills, like amoxicillin or metformin, bioequivalence is easy to prove. You swallow it. You measure blood levels. Done. But what about a cream that goes on your skin? Or an inhaler that delivers medicine deep into your lungs? Or a slow-release capsule that needs to work over 12 hours? These are complex products. Standard blood tests don’t capture how well they work in the body. The FDA admits this. In its 2022 draft guidance, it said current methods "may not adequately reflect therapeutic equivalence" for these kinds of drugs.

That’s why you’ll see "B" codes on topical steroids, asthma inhalers, or injectable biologics. The drug might be chemically identical. The issue is proving it behaves the same way in real people. Pharmacists know this. A 2022 survey found that 42% of doctors were confused by "B" codes, and 28% had cases where a pharmacist refused to substitute a product that was actually fine to swap.

How Pharmacists Use the Orange Book Every Day

If you’ve ever wondered how your pharmacist knows whether to swap your brand-name drug for a generic, here’s the answer: they open the Orange Book. It’s not a book anymore-it’s a searchable online database updated monthly. Pharmacists check it before filling prescriptions. In fact, 87% of community pharmacists say the TE codes make their job easier.

Here’s how it works in practice:

- The prescriber writes a brand-name drug, say, Lipitor.

- The pharmacy checks the Orange Book for the TE code.

- If it’s "AB," they can substitute any other "AB"-rated atorvastatin without asking.

- If it’s "B," they must call the doctor or leave the brand in place.

This isn’t optional. Forty-nine states allow pharmacists to substitute "A"-rated generics automatically. Only one state requires the doctor’s permission every time. In 38 states, if a "B"-rated product is substituted, the pharmacist must notify the prescriber. That’s why you sometimes get a call after picking up your prescription.

On average, pharmacists spend 2.7 minutes per prescription checking these codes. That adds up. In 2023, that process saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $1.2 billion.

What Happens When a Drug Gets a "B" Rating

A "B" rating doesn’t mean the drug is unsafe. It means the FDA needs more data. Sometimes, that data comes from new studies. Sometimes, it comes from real-world use. For example, a topical cream might get a "BT" code because measuring skin absorption is hard. But if enough doctors report that patients do just as well on the generic as the brand, the FDA may reclassify it.

Between 2018 and 2022, the number of "B"-rated applications for complex generics rose by 22%. That’s because more companies are trying to make generics for tricky drugs-like inhalers, injectables, and skin treatments. The FDA is responding by creating more detailed guidelines called Product-Specific Guidance (PSG) documents. There are now over 1,850 of them, each telling manufacturers exactly how to prove their drug works like the brand.

By 2027, the FDA aims to reduce "B" ratings for complex generics by 30%. That means more generics will get "A" codes-and more people will have access to affordable versions of expensive medications.

Why This Matters for You

Generic drugs save patients and insurers $370 billion every year in the U.S. But that only works if people can trust the substitution system. If you’re on a medication that’s been switched to a generic, you might wonder: "Is this really the same?" The answer is yes-if it has an "A" code. The FDA doesn’t approve these lightly. They’ve tested them. They’ve compared them. They’ve watched how they perform in real people.

If you see a "B" code on your generic, don’t panic. It doesn’t mean it won’t work. It just means the science isn’t settled yet. Talk to your pharmacist or doctor. Ask: "Why is this rated B?" Sometimes, the answer is simple: "We’re still gathering data." Other times, it might mean your condition needs the brand for now.

The system isn’t perfect. But it’s the best we have. And it’s working. Over 12,600 of the 14,000 drugs listed in the 2023 Orange Book have an "A" rating. That’s 90%. For most people, the generic is just as good-and a lot cheaper.

What’s Next for Therapeutic Equivalence?

The FDA isn’t stopping. It’s working on new ways to evaluate complex drugs. One idea? Use real-world data from patient records-not just lab tests from healthy volunteers. Another? Better testing for inhalers and injectables. The goal is simple: make more generics eligible for substitution without sacrificing safety.

For now, if you’re taking a generic drug, check the label. Look for the TE code. If it starts with "A," you’re covered. If it starts with "B," ask questions. You have the right to know why.

What does an "A" rating mean for a generic drug?

An "A" rating means the FDA has determined the generic drug is therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name version. It has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration, and it has passed bioequivalence testing. This means it can be substituted for the brand without needing a doctor’s approval in most states.

Can I always substitute a generic with an "A" rating?

In 49 U.S. states, yes. Pharmacists can substitute an "A"-rated generic without contacting your doctor. The only exception is if your doctor writes "Dispense as Written" or "Do Not Substitute" on the prescription. Some states also require pharmacists to notify you if substitution occurs, but they don’t need your permission.

Why do some generics have a "B" rating if they seem the same?

A "B" rating means the FDA doesn’t have enough evidence to confirm the generic is interchangeable. This often happens with complex products like inhalers, topical creams, or extended-release capsules, where traditional blood tests don’t fully show if the drug behaves the same way in the body. The drug may still be safe and effective, but the testing method isn’t reliable enough yet to give it an "A".

Do other countries use the same system as the FDA?

No. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and other international regulators don’t use a letter-code system like the FDA’s. Instead, they publish detailed scientific reviews for each generic application. The FDA’s system is unique because it gives pharmacists a clear, immediate signal-"A" or "B"-to act on without needing to read a 50-page report.

Are over-the-counter (OTC) drugs rated with therapeutic equivalence codes?

No. The FDA’s therapeutic equivalence system only applies to prescription drugs. OTC medications, like ibuprofen or antacids, are not evaluated or coded in the Orange Book. This is because they’re generally considered low-risk and widely used, so substitution is already common and accepted without formal oversight.

What You Should Do Next

If you’re taking a generic drug, check your prescription label or ask your pharmacist: "What’s the TE code?" If it’s "A," you’re good. If it’s "B," ask why. Don’t assume it’s unsafe-just understand the uncertainty. And if you’re switching from brand to generic, give it a few weeks. Your body might need time to adjust, even if the drugs are equivalent. Most people don’t notice a difference. But if you do, talk to your doctor. Your health is worth the conversation.

Carla McKinney

February 13, 2026 AT 21:59Let’s be real-the FDA’s Orange Book is less a scientific bible and more a bureaucratic Rube Goldberg machine. AB ratings? Sure. But how many of those were approved because a company paid for a 12-patient bioequivalence study at 3 a.m. in a lab with expired equipment? I’ve seen the data. The 80%-125% window is a joke. That’s a 45% variance. One pill could be 20% under, another 25% over. You call that "equivalent"? I call it a lottery.

And don’t get me started on the "B" ratings. Topical creams? Inhalers? Of course the current methods don’t work. We’re measuring blood levels for drugs that don’t enter the bloodstream. The FDA knows this. They just don’t want to admit they’re flying blind on 30% of the market. Meanwhile, patients are getting stuck with brand-name prices because the system is too cowardly to adapt.

It’s not about cost. It’s about control. The system favors manufacturers who can afford 18-month bioequivalence trials. Small labs? Out. The real threat to public health isn’t generics-it’s the FDA’s refusal to modernize its tools.

And yes, I’ve reviewed the 2022 draft guidance. The language is vague. The timelines are nonexistent. This isn’t science. It’s PR dressed up in lab coats.

Ojus Save

February 15, 2026 AT 07:54yo so like i read this whole thing and wow the orange book is kinda wild fr

so if its AB1 or whatever u can only swap within that group? so if i got a generic from one company and then another one comes in but its AB2… u cant swap? like even if theyre the same drug? thats so weird lol

also why do inhalers get a BT code? is it bc u cant just measure blood like u do with pills? i mean i get it but its still kinda wild that we dont have a better way to test this. like… we have drones that deliver pizza but we cant measure how a puff of medicine gets into lungs? 🤔

Annie Joyce

February 17, 2026 AT 07:02As a pharmacist who’s been doing this for 14 years, I can tell you-the TE codes are the unsung heroes of affordable healthcare. People think it’s all about saving money, but honestly? It’s about trust. When a patient comes in with a prescription for Lipitor and I hand them atorvastatin, I need to know it’s not just chemically similar-it’s clinically identical.

And yeah, the "B" codes? Frustrating. I had a guy last week get a B-rated inhaler. He was furious. "My old one worked fine!" I told him: "It probably did. But the FDA doesn’t have the data to prove your new one will too." He left mad. Came back two days later with a thank-you note. Said he tried it, didn’t notice a difference, and now he’s saving $80 a month.

The system isn’t perfect. But it’s the most transparent, science-backed system we’ve got. And it’s saving billions. Don’t trash it because it’s not flawless. Help fix it. We need better tools for complex delivery systems-not more conspiracy theories.

Rob Turner

February 18, 2026 AT 04:01Interesting stuff. I’ve been on a few generics over the years-mostly for blood pressure-and never noticed a difference. But I live in the UK, where we don’t have this letter system. We just get a green light if the EMA says it’s equivalent. No "AB3" or "BX" nonsense.

It makes me wonder: is the FDA’s system actually more precise… or just more complicated? We rely on detailed scientific reviews, which are public and thorough. Here, pharmacists just glance at a letter. Is that enough?

Also-side note-why is it called the "Orange Book"? 🤔 I’ve always assumed it was a metaphor. Turns out it’s literally an orange cover. Who knew? 🍊

Luke Trouten

February 19, 2026 AT 00:00The real triumph here is that we’ve managed to create a system that balances innovation, safety, and accessibility. The fact that over 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics speaks volumes. We don’t need perfection-we need progress.

The "B" ratings aren’t failures. They’re invitations-to do better science, to invest in better measurement tools, to fund more real-world studies. The FDA’s move toward Product-Specific Guidance documents is exactly what’s needed. Instead of dismissing the system because it’s imperfect, we should be pushing for its evolution.

And yes, the 80%-125% window is wide. But it’s not arbitrary. It’s based on decades of pharmacokinetic data and statistical confidence intervals. It’s not perfect, but it’s the gold standard because it’s been validated across millions of patients.

Let’s not confuse the system’s complexity with its failure. It’s working. We’re just not done improving it.

christian jon

February 19, 2026 AT 07:27THIS IS A SCAM. A COMPLETE AND UTTER SCAM.

Did you know that 73% of "AB"-rated generics are manufactured in India and China? Did you know that the FDA inspects less than 2% of those facilities? I’ve seen the reports. The FDA doesn’t "test" anything. They rely on paperwork. Paperwork. From factories where workers are paid $2 a day to stamp pills with fake batch numbers.

And now they’re telling us to trust a LETTER? "A"? What does that even mean?! That the CEO of the company had dinner with a FDA official? That’s how these codes get assigned.

My cousin got a generic for her seizure med. It was "AB". She had three seizures in two weeks. The brand? Zero. Zero. She’s lucky she didn’t die.

They’re all connected. Big Pharma. The FDA. The pharmacies. They want you on generics so they can make billions. And you’re just supposed to trust a stupid orange book? I’m not buying it. I’m not buying ANYTHING labeled "AB" anymore.

WAKE UP, PEOPLE. THEY’RE KILLING US WITH SAVINGS.

P.S. If you think I’m being dramatic… go read the 2021 FDA whistleblower report. It’s not in the Orange Book. But it’s out there. And it’s terrifying.

Suzette Smith

February 19, 2026 AT 09:51Actually, I think the "B" rating is the smarter choice. Why rush to substitute? If we’re not 100% sure, why not just stick with what we know? I’ve been on the same brand for 12 years. Never had an issue. Why risk it for $15 savings? The system should encourage caution-not speed. We’re not trying to win a race here.

Autumn Frankart

February 19, 2026 AT 18:16They’re lying. All of it. The FDA doesn’t test anything. The "Orange Book"? It’s a cover. The real system is run by a shadow consortium of pharmaceutical CEOs. The "A" and "B" codes? They’re just codes to control which drugs you can afford.

Did you know the FDA’s bioequivalence window was changed in 2017? Right after the big merger between Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson? Coincidence? I think not.

And why are inhalers and creams rated "B"? Because they’re the ones that are hardest to fake. The big companies don’t want generics on those. So they let the FDA keep the "B" rating to scare people away.

They want you to think you’re saving money… but you’re being locked into brand-name prices. The "B" rating? It’s not about science. It’s about control. They don’t want you to know how easy it would be to make a real generic for inhalers. But they’re not letting you.

Ask yourself: why does the FDA refuse to publish the raw data? Why is the Orange Book paywalled? Why do pharmacists have to sign NDAs before accessing it?

It’s not a book. It’s a prison.

Pat Mun

February 20, 2026 AT 19:05Wow. I just spent 20 minutes reading this and I’m honestly amazed. I never thought about how much goes into deciding whether my generic blood pressure pill is safe to swap. I just assumed it was all the same.

But now I get it. The letter codes? They’re like traffic lights for your health. Green means go. Yellow means slow down and ask questions. Red means stop and call your doctor.

I’ve been on a generic for years. Always thought it was just cheaper. Now I realize it’s because a whole team of scientists ran tests, collected blood samples, and made sure it behaved the same way in my body as the brand. That’s wild.

And the fact that pharmacists spend 2.7 minutes per prescription checking this? That’s a lot of time. But it’s worth it. That’s how we save $1.2 billion a year. That’s not just money-that’s lives. More people can afford their meds. More people stay healthy.

Yeah, the system’s not perfect. The "B" ratings are confusing. But we’re moving toward better science. Real-world data. Better testing for inhalers. That’s progress.

So next time you get a prescription, don’t just grab the generic. Look at the code. Ask why. Be curious. Because this system? It’s quietly saving millions of people every day. And we don’t even know it.