Multiple sclerosis isn’t just a neurological condition-it’s an internal betrayal. Your own immune system, designed to protect you, turns against your brain and spinal cord. It sees the protective coating around your nerves as a threat and starts tearing it apart. This isn’t hypothetical. It’s happening right now in the bodies of nearly 3 million people worldwide. And for those living with it, the effects are real, unpredictable, and deeply personal.

What Happens When Your Immune System Attacks Your Nerves

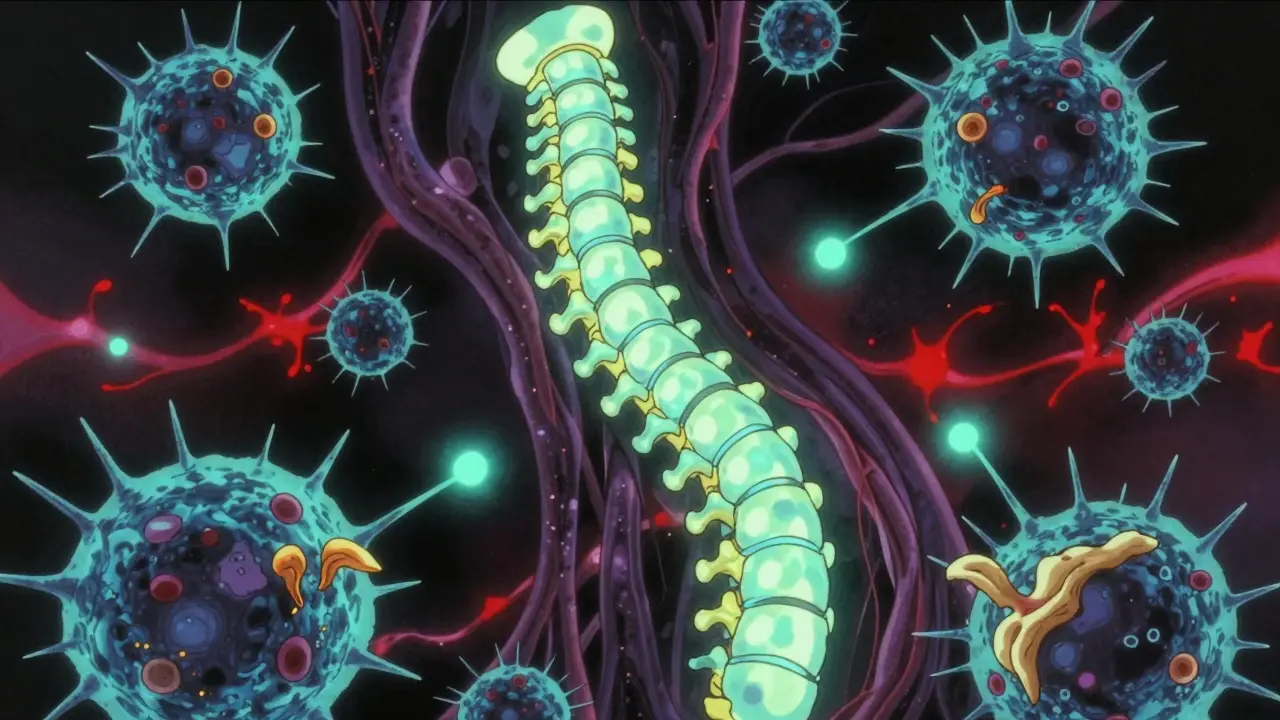

At the heart of multiple sclerosis is a simple, devastating process: demyelination. Your nerves are wrapped in a fatty insulator called myelin. Think of it like the plastic coating on an electrical wire. It lets signals-your thoughts, your movements, your vision-travel fast and clear. In MS, immune cells breach the blood-brain barrier, a normally tight seal that keeps harmful substances out of your central nervous system. Once inside, they target myelin. T cells, B cells, and macrophages swarm the area, stripping away this insulation. The result? Signals stutter, fade, or disappear entirely.

This isn’t random damage. It follows patterns. In some cases, T cells dominate the attack. In others, antibodies from B cells cling to the myelin, marking it for destruction. Microglia, the brain’s own immune cells, get activated and start chewing up damaged tissue. And here’s the cruel twist: the body tries to repair itself. But the inflammatory environment is so toxic that new myelin rarely forms. Scar tissue-sclerosis-builds up instead. That’s where the name comes from: multiple scars in the nervous system.

Why Does This Happen?

No one person gets MS for the same reason. It’s a perfect storm of genes and environment. You might carry certain genetic markers that make you more vulnerable. But genes alone don’t cause it. Something has to trigger it. And the biggest suspect? Epstein-Barr virus. People who’ve had this common cold-like virus are 32 times more likely to develop MS. That’s not a small risk-it’s a massive one.

Vitamin D deficiency plays a role too. People living farther from the equator, where sunlight is weaker, have higher MS rates. Low vitamin D levels are linked to a 60% increased risk. Smoking? That raises your chance of progression by 80%. And it’s not just lifestyle-it’s timing. Exposure to these triggers during adolescence and early adulthood seems to be the critical window.

Women are two to three times more likely to get MS than men. Why? Hormones, immune system differences, and possibly how genes interact with estrogen are all being studied. But the bottom line: if you’re a woman in your 20s or 30s, your risk is higher than most people realize.

What Does It Actually Feel Like?

MS doesn’t have one face. It wears many. One person might lose vision in one eye for weeks-optic neuritis-then recover. Another might feel numbness in their feet, like walking on cotton. Some describe electric shocks down their spine when they bend their neck. That’s Lhermitte’s sign, a classic symptom caused by damaged nerves in the cervical spine.

Fatigue hits 80% of people with MS. Not just tiredness-bone-deep exhaustion that doesn’t improve with rest. Walking becomes harder. Balance slips. Bladder control falters. Cognitive fog creeps in: forgetting names, struggling to find words, losing focus mid-sentence. These aren’t imagined. They’re direct results of myelin loss in specific brain regions. When the signal from your motor cortex can’t reach your leg muscles, you stumble. When the optic nerve is scarred, your vision blurs. When the brainstem is affected, you feel dizzy or nauseous.

And it’s not always dramatic. Sometimes it’s subtle-a tingling finger, a delayed reaction, a moment of unexplained weakness. That’s why MS is so hard to diagnose. Symptoms come and go. You might think it’s stress, a pinched nerve, or just getting older. But if these episodes repeat, especially in young adults, it’s worth asking: could this be MS?

The Two Main Flavors of MS

Most people-about 85%-start with relapsing-remitting MS. That means flare-ups, followed by recovery. A flare-up, or relapse, lasts days or weeks. New symptoms appear. Old ones return. Then, slowly, things improve. But not always completely. Each attack leaves behind some damage. Over time, those tiny losses add up.

The other 15% have primary progressive MS. No relapses. No remissions. Just a steady, slow decline. Walking gets harder. Strength fades. Balance worsens. There’s no sudden crash-just a relentless slide. This form is harder to treat. The immune attack is quieter, more chronic. It’s not about big inflammatory storms. It’s about slow, smoldering nerve death.

And then there’s secondary progressive MS. Many with relapsing-remitting MS eventually shift into this phase. The flare-ups become less frequent, but the decline continues. The immune system isn’t as active, but the damage is already done. The nervous system can’t keep up. This transition usually happens 10 to 20 years after diagnosis.

What Treatments Exist Today?

Treatment today isn’t about curing MS. It’s about stopping the attack before it destroys more nerves. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are the cornerstone. They don’t fix damaged tissue-but they can stop new damage.

Ocrelizumab targets B cells. It’s one of the few drugs approved for both relapsing and primary progressive MS. In trials, it cut relapses by 46% and slowed disability progression by 24%. Natalizumab blocks immune cells from crossing into the brain. It’s powerful-reducing relapses by 68%-but risky. One in a thousand people develop a rare brain infection called PML. That’s why doctors test for the JC virus before prescribing it.

Newer drugs like siponimod and cladribine work by calming the immune system in different ways. They’re not perfect. Side effects range from headaches to liver stress. But they work. And they’ve changed the game. Twenty years ago, half of untreated MS patients needed a cane within 15 years. Today, with early treatment, that number has dropped to 30%.

And then there’s the hope on the horizon: remyelination. Researchers are testing drugs like clemastine fumarate, which showed a 35% improvement in nerve signal speed in early trials. If we can teach the body to rebuild myelin, we might not just slow MS-we might reverse some of its damage.

What’s on the Horizon?

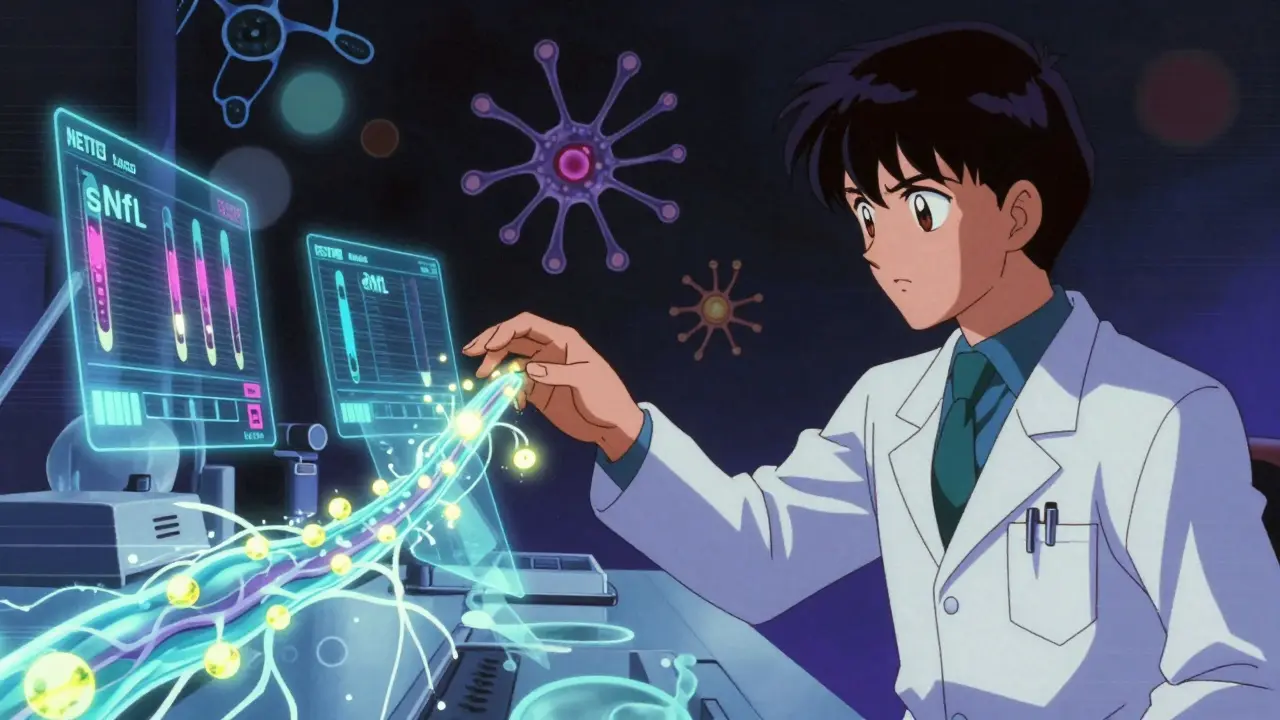

Science is moving fast. One breakthrough? Identifying biomarkers. Blood tests for neurofilament light chain (sNfL) can now detect active nerve damage before symptoms appear. Levels above 15 pg/mL mean inflammation is happening-even if you feel fine. That’s huge. It lets doctors adjust treatment before more damage occurs.

Another target? Dendritic cells. These immune sentinels in the brain are now known to actively present myelin fragments to T cells, keeping the attack alive. Blocking them could shut down the cycle. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), sticky webs released by immune cells, are also being studied. They help break down the blood-brain barrier. In 78% of MS relapses, NET markers spike. Could stopping NETs prevent attacks?

The International Progressive MS Alliance has poured $65 million into research since 2014. Projects span 14 countries. The goal? Not just to manage MS-but to end it.

Living With It

MS isn’t a death sentence. It’s a lifelong condition-with good days and bad. Many people work, raise families, travel, and live full lives. Physical therapy, exercise, stress management, and a healthy diet help. Avoiding smoking and getting enough vitamin D aren’t just advice-they’re part of treatment.

Support matters. Online communities like Reddit’s r/MS are full of people sharing how they cope: using voice-to-text when fatigue hits, wearing compression socks for leg weakness, adjusting work hours to avoid overheating. These aren’t small things. They’re survival tactics.

And hope? It’s real. Every year, new drugs come to market. Every year, researchers learn more. We’re not there yet. But we’re closer than we’ve ever been.

Is multiple sclerosis contagious?

No, MS is not contagious. You can’t catch it from someone else through touch, air, or bodily fluids. It’s an autoimmune condition, meaning it arises from your own immune system misfiring. While viruses like Epstein-Barr may trigger it in genetically prone individuals, the disease itself cannot be passed from person to person.

Can you die from multiple sclerosis?

MS itself is rarely fatal. Most people with MS live near-normal lifespans. But complications from severe disability-like pneumonia from difficulty swallowing, urinary tract infections, or pressure sores-can be life-threatening if not managed. Good care, regular checkups, and staying active reduce these risks significantly.

Does stress make MS worse?

Stress doesn’t cause MS, but it can trigger flare-ups. High stress levels raise inflammation in the body, which can worsen immune activity in the nervous system. Many people report relapses following major life events-job loss, divorce, bereavement. Managing stress through mindfulness, therapy, or exercise is a key part of staying stable.

Can diet cure multiple sclerosis?

No diet can cure MS. But what you eat can influence inflammation and overall health. Diets rich in omega-3s, antioxidants, and fiber-like the Mediterranean diet-may help reduce fatigue and improve quality of life. Avoiding processed foods, sugar, and saturated fats is also recommended. Diet supports treatment-it doesn’t replace it.

Is exercise safe if you have MS?

Yes, and it’s strongly encouraged. Exercise improves strength, balance, mood, and bladder control. Swimming, yoga, walking, and stationary cycling are popular choices. Avoid overheating-heat can temporarily worsen symptoms. Work with a physical therapist to build a routine that fits your abilities. Many people with MS find exercise helps them feel more in control of their bodies.

Can you have children if you have MS?

Yes. MS doesn’t affect fertility. Many women experience fewer relapses during pregnancy, especially in the second and third trimesters. However, some disease-modifying therapies must be stopped before conception. Planning with your neurologist is essential. Postpartum, relapse risk increases slightly, but with proper support, most women manage well.

What Comes Next?

If you’ve been diagnosed, the next step isn’t fear-it’s action. Find a neurologist who specializes in MS. Start treatment early. Track your symptoms. Ask about sNfL blood tests. Join a support group. Learn what helps you feel your best. MS is complex, but you’re not alone. And science is moving faster than ever.

If you’re worried you might have it-pay attention to your body. A sudden change in vision, numbness that doesn’t go away, or unexplained fatigue lasting weeks? Get checked. Early diagnosis means early treatment. And early treatment means more years of living well.

Cassie Widders

January 12, 2026 AT 12:51My aunt had MS for 20 years. She never used a cane, kept working, even traveled to Japan. It’s not a death sentence, just a weird new normal.

Windie Wilson

January 13, 2026 AT 18:48So let me get this straight - your body turns into a traitor, the virus that gave you a cold in 2003 is now the reason you can’t feel your toes, and the only cure is paying $100K a year for drugs that make you feel like a zombie? Sounds like a sci-fi movie written by a disgruntled insurance agent.

Ben Kono

January 14, 2026 AT 17:04My cousin got diagnosed last year and now she’s on some new drug that costs more than her car and she still gets dizzy every morning. I don’t know why they even bother with these meds if you’re just gonna feel like crap anyway. They’re selling hope like it’s a subscription box

Daniel Pate

January 16, 2026 AT 16:49The real tragedy isn’t just the demyelination - it’s the systemic failure to treat MS as a neurological emergency. We treat cancer like a war, but MS is treated like a chronic inconvenience. Why aren’t we pouring billions into remyelination research like we do for Alzheimer’s? The biology is clearer. The targets are identified. We’re not lacking science - we’re lacking urgency.

And the Epstein-Barr link isn’t just correlation. It’s causation waiting for the right genetic trigger. We’ve known this for a decade. Why hasn’t a vaccine been prioritized? Because pharmaceuticals make more money selling lifelong DMTs than preventing the disease in the first place.

The blood-brain barrier isn’t just a wall - it’s a checkpoint that’s been hacked. We need immune system firewalls, not just bandaids on the damage. And yes, vitamin D matters - but it’s not a magic bullet. It’s one variable in a multivariate system of immune dysregulation.

We’re decades behind where we should be. This isn’t just medical neglect - it’s ethical negligence.

Rebekah Cobbson

January 17, 2026 AT 19:27If you’re newly diagnosed, don’t panic. Find a good neurologist who listens. Start moving - even if it’s just stretching in bed. Connect with others online. You’ll find people who get it. And yes, the fatigue is real, but so is your strength. You’re not broken. You’re adapting.

And if you’re reading this and you’re not affected yet - be kind. You don’t know who’s fighting invisible battles every day.

Audu ikhlas

January 19, 2026 AT 18:13USA and Europe make MS sound like some elite disease but in Nigeria we dont even have MRI machines in most hospitals. People die from this because they cant get diagnosed. You all talk about drugs and research but we talk about surviving. Your science is useless if it dont reach the poor.

Cecelia Alta

January 20, 2026 AT 19:13Okay so let me summarize this 10,000 word essay: your immune system is a toxic ex who won’t leave you alone, your nerves are like frayed phone cables, and the only thing keeping you from turning into a human paperweight is a $12,000 pill that gives you diarrhea and makes you cry during commercials? And the worst part? The drug companies are literally laughing all the way to the bank because you’re gonna need this for the rest of your life. And they call this healthcare? I swear if I had MS I’d just move to a cabin in the woods and eat turmeric and hope for the best. At least then I’d be happy and not broke.

Also, I’m 32, female, live in Minnesota, and I’ve had a weird tingling in my left pinky for three weeks. I’m definitely getting MS. I’ve already started writing my will and ordering a wheelchair on Amazon.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘exercise helps’ advice. Yeah, great, let me just hop on the treadmill when my legs feel like wet noodles and my brain is stuck in molasses. I’m not lazy, I’m neurologically compromised. But sure, I’ll just ‘push through’ like some inspirational poster says.

Also, why is everyone always talking about vitamin D? Do we all just forget that most people live in cities and work inside? We’re not bears. We can’t hibernate in the sun. And no, taking a vitamin D pill doesn’t magically undo 20 years of indoor living and fluorescent lighting. This whole thing is a mess.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘you can still have kids’ thing. Yeah, great, I’ll give birth to a perfectly healthy baby while my own body is falling apart. Thanks for the encouragement, I’ll just add ‘maternal guilt’ to my list of MS symptoms.

And why is no one talking about how the word ‘progressive’ sounds like a slow-motion death sentence? Like, ‘Oh, your disease is progressive’ - that’s not a medical term, that’s a horror movie tagline.

And can we just acknowledge that the people who write these articles have never had MS? They’re all doctors or journalists who read one study and now they think they’re experts. I’d love to see a post written by someone who’s actually lived with this for 15 years and isn’t trying to sell me hope or a supplement.

Also, I just googled ‘MS and sarcasm’ and it came up with zero results. That’s the real tragedy.

Amanda Eichstaedt

January 22, 2026 AT 13:02I’ve been living with RRMS for 11 years. I’ve had three relapses. I’ve tried five DMTs. I’ve had MRIs that looked like a star map. I’ve cried in parking lots. I’ve laughed until I cried at a meme about walking like a penguin. I’ve had people tell me I look fine so I must be faking. I’ve had people tell me I’m brave for just getting out of bed.

Here’s what no one says: you don’t have to be brave. You don’t have to be inspirational. You don’t have to turn your diagnosis into a TED Talk. You just have to show up. Some days, that’s enough.

And yes - the fatigue is worse than any sleep deprivation you’ve ever experienced. It’s not laziness. It’s your nervous system running on fumes.

And yes - you can still fall in love. You can still travel. You can still be angry, tired, messy, and human.

MS didn’t take my life. It just changed the way I live it.