Medication Safety Checker for Seniors

Medication Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps identify potential medication risks for older adults using principles from the Beers Criteria. Enter medications you're taking to see if any combinations pose risks of falls, confusion, or other serious side effects.

Current Medications

Why Older Adults React Differently to Medications

When you’re 70, a pill that worked fine at 40 can make you dizzy, confused, or fall down. It’s not that the medicine changed. Your body did. As we age, how our bodies handle drugs shifts in ways most people don’t expect. Liver blood flow drops by 30-40% between ages 25 and 75. Kidneys filter slower-about 0.8 mL/min/1.73m² less each year after 40. Body fat climbs from 25% in your 30s to 35-40% by 70. These aren’t minor tweaks. They mean drugs stay in your system longer, build up more easily, and hit harder.

Take diazepam. At 30, it clears in about 24 hours. At 75, it lingers for days. That’s why an older person on the same dose as a younger one ends up groggy, unsteady, or confused. It’s not laziness. It’s pharmacology. The same goes for painkillers, sleep aids, and even common blood pressure pills. What was once safe can become dangerous.

The Hidden Dangers of Taking Too Many Pills

Most older adults aren’t on one or two meds. They’re on five, seven, even ten. This isn’t just common-it’s the norm. Doctors treat heart disease, arthritis, diabetes, and sleep problems separately. But they don’t always look at the full picture. That’s where polypharmacy becomes a silent threat.

When five or more drugs mix, interactions multiply. Corticosteroids plus NSAIDs? That’s a 15-times higher risk of a bleeding ulcer. Anticoagulants like warfarin mixed with ibuprofen? Hospitalization risk spikes. Even something as simple as an OTC antihistamine for allergies can worsen confusion or cause urinary retention in seniors.

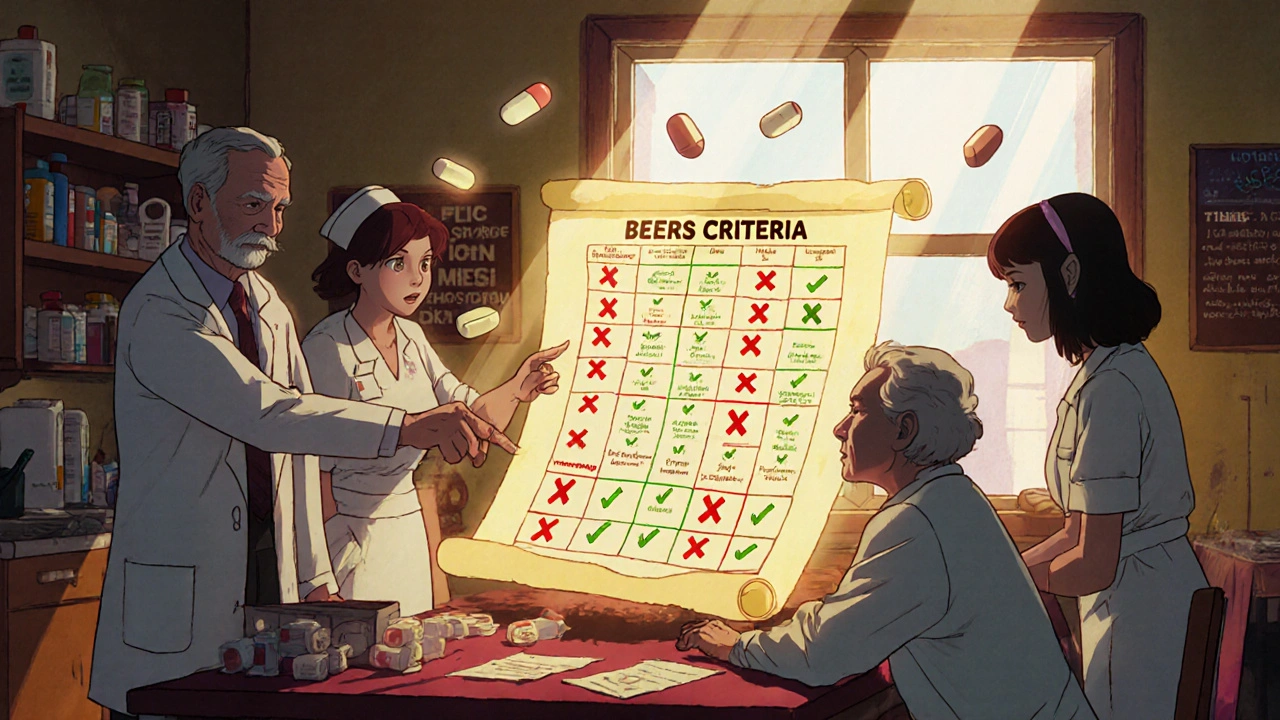

One study found that 20-30% of falls in people over 65 are directly tied to medication side effects. Not bad balance. Not slippery floors. A pill. That’s why the American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria exists-to flag drugs that are riskier than they’re worth for older adults. Medications like megestrol, glyburide, and sliding-scale insulin are on that list. So are certain SSRIs if you’ve already had a fall or fracture.

Side Effects That Don’t Look Like Side Effects

Younger people get stomach upset, rashes, or headaches when a drug doesn’t agree with them. Older adults? They get quieter. Slower. More forgetful. They stop eating. They fall. They don’t recognize their own grandchildren. These aren’t signs of dementia or aging-they’re red flags for a bad drug reaction.

Confusion isn’t just "getting old." It can be caused by anticholinergics like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), which many seniors still take for sleep or allergies. Dizziness isn’t normal. It might be from blood pressure meds that dropped too low. Weight loss? Could be from a thyroid pill that’s too strong. Memory loss? Could be from long-term use of benzodiazepines like lorazepam.

Doctors often miss these because they’re not classic side effects. That’s why experts now say: if an older patient suddenly changes behavior, ask: "What’s new in their meds?" Not just prescriptions-vitamins, supplements, herbal teas, and over-the-counter pain relievers count too.

Drugs to Avoid in Seniors (And Why)

Some medications should be avoided in older adults-not because they’re useless, but because safer options exist. The 2019 update to the Beers Criteria made this clearer than ever.

- Pentazocine: A painkiller that causes hallucinations and confusion more than other opioids. It’s not worth the risk.

- Propoxyphene: Withdrawn in the U.S. in 2010, but still found in some older prescriptions. Offers little pain relief but carries serious heart and brain risks.

- Indomethacin: An NSAID with the highest rate of brain-related side effects among its class. Headaches, dizziness, and delirium are common.

- Phenylbutazone: Rarely used now, but still around in some places. Can wipe out white blood cells and cause life-threatening blood disorders.

- Glitazones (like pioglitazone): Used for diabetes, but they cause fluid retention-dangerous if you have heart failure.

- Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Used for Alzheimer’s, but they can slow the heart too much in people with a history of fainting.

These aren’t "bad" drugs. They’re drugs that need extra caution. For example, a senior with chronic pain might do better on acetaminophen and physical therapy than on an opioid. A diabetic might control blood sugar with diet and metformin instead of glyburide, which causes dangerous low blood sugar.

What You Can Do: Practical Steps for Safer Medication Use

Safe medication use in older adults isn’t just the doctor’s job. It’s a team effort-and you’re part of it.

- Keep a full, updated list of everything you take: prescriptions, OTC meds, vitamins, supplements, and herbal products. Bring it to every appointment-even if you think it’s "not important."

- Ask: "Can anything be stopped?" Every time a new drug is added, ask your doctor or pharmacist: "Is there one I can stop?" Many seniors can safely reduce their pill count without losing benefits.

- Watch for new symptoms after starting a new drug. If you feel foggy, unsteady, or less hungry, don’t brush it off. Call your provider. Say: "This started after I began [medication]."

- Use one pharmacy for all prescriptions. Pharmacists can spot dangerous interactions you might miss. They’re trained to catch what doctors overlook.

- Use pill organizers if you’re on multiple meds. But don’t just rely on them. Check the labels. Some pills look alike. Confusion happens.

Also, don’t assume side effects are "just part of aging." If you’re falling more, forgetting names, or feeling unusually tired, it could be your meds. Speak up.

Who Should Be Involved in Managing Senior Medications?

Managing medications for older adults isn’t a one-person job. It takes a team.

Doctors diagnose and prescribe. But pharmacists? They’re the unsung heroes. They check for interactions, spot duplications, and help simplify regimens. Nurses help monitor symptoms and educate patients. Caregivers notice changes in behavior, appetite, or mobility that patients themselves might not report.

Many hospitals now use medication therapy management (MTM) programs, where pharmacists sit down with seniors for 30-minute reviews. These programs cut hospital visits by up to 40% in some studies. But they’re not available everywhere. If yours doesn’t offer one, ask your doctor to refer you to a geriatric pharmacist.

And don’t underestimate the role of family. A daughter who notices her mom isn’t eating or a grandson who sees his grandfather stumbling? They’re often the first to catch a problem. Tell them: "Your eyes matter. Keep watching."

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Now More Than Ever

By 2030, one in five Americans will be over 65. That’s 95 million people. And they’re taking more meds than any other age group. In 2020, seniors made up just 16.8% of the U.S. population but accounted for nearly 34% of all prescription drug spending.

Adverse drug reactions send over 100,000 older adults to the hospital every year. Half of those are preventable. The cost? Around $3.5 billion annually in the U.S. alone.

Health systems are waking up. Medicare now tracks inappropriate prescribing through HEDIS quality measures. The Beers Criteria are built into electronic health records. But tools don’t fix problems-people do.

It’s not about cutting all meds. It’s about keeping what works and ditching what doesn’t. A senior on five pills might do just as well on two-with fewer falls, clearer thinking, and better quality of life. That’s the goal.

What’s Next? Personalized Medicine and the Future

The future of senior medication safety isn’t just about avoiding bad drugs-it’s about choosing the right ones for the right person.

Researchers are now looking at pharmacogenomics: how your genes affect how you process drugs. Some people metabolize warfarin slowly. Others break down codeine too fast. These differences become more important with age.

The National Institute on Aging has made optimizing medication use in older adults a top research priority. New tools like the STOPP/START criteria (2019 version) help doctors spot both inappropriate prescriptions and missed opportunities-like not prescribing a flu shot or a bone-strengthening drug when needed.

But until personalized genetic testing becomes routine, the best tool we have is still simple: ask questions. Listen. Review. Adjust. And never assume a side effect is just "getting older."

Sherri Naslund

November 18, 2025 AT 11:34Ashley Miller

November 19, 2025 AT 09:03Martin Rodrigue

November 19, 2025 AT 14:11Will Phillips

November 20, 2025 AT 13:36Tyrone Luton

November 21, 2025 AT 17:44Jeff Moeller

November 23, 2025 AT 13:48Herbert Scheffknecht

November 23, 2025 AT 20:48Jessica Engelhardt

November 25, 2025 AT 19:22