GERD Symptom Checker

Check Your GERD Symptoms

Answer a few questions to assess your symptoms and understand if GERD might be the cause of your epigastric pain.

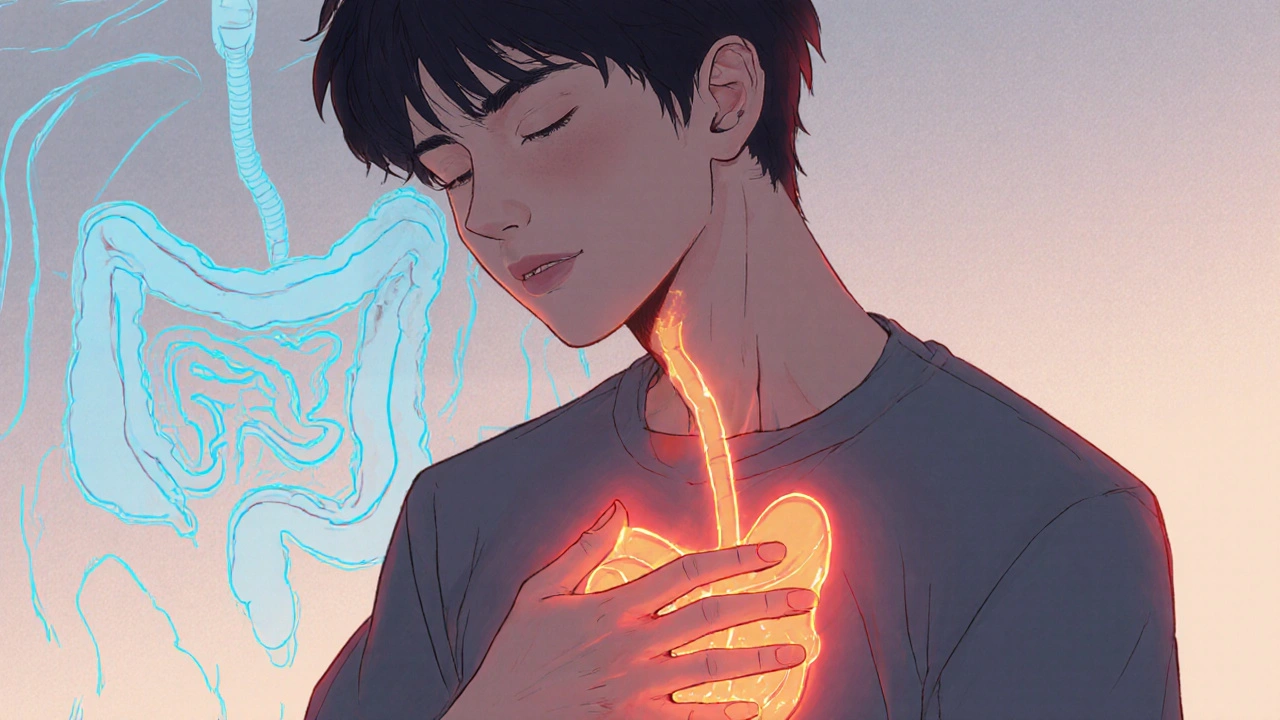

When you feel a burning or gnawing ache right under your breastbone, you’re experiencing Epigastric Pain - a symptom that can stem from many sources. One of the most common culprits is Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD), the chronic backflow of stomach acid into the esophagus. Understanding how these two are linked is the first step toward relief. This guide walks you through the anatomy, why the pain shows up, how doctors pinpoint the cause, and which treatments actually work.

Key Takeaways

- Epigastric pain can be a symptom of GERD, but it also signals other stomach or pancreatic issues.

- Accurate diagnosis combines symptom questionnaires, endoscopy, and 24‑hour pH monitoring.

- Lifestyle changes - weight loss, diet tweaks, and head‑of‑bed elevation - often cut reflux episodes in half.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) are the first‑line medication, but long‑term use requires monitoring.

- Surgery such as laparoscopic fundoplication is reserved for severe, medication‑refractory cases.

Understanding Epigastric Pain

The epigastric region sits just below the sternum and above the umbilicus. It houses the lower esophagus, stomach, duodenum, and part of the pancreas. Because many organs share this space, pain here is a classic “catch‑all” symptom.

Common causes include:

- Gastric ulcer or erosion

- H. pylori infection

- Nonsteroidal Anti‑inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) irritation

- Pancreatitis

- Gallbladder disease

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Distinguishing GERD‑related pain from other origins often hinges on timing (after meals vs. fasting), aggravating factors (lying down, bending), and associated symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, or sour taste.

What Is GERD?

GERD occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter (Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES)) fails to close properly, allowing acidic stomach contents to splash back into the esophagus. Chronic exposure damages the esophageal lining, leading to inflammation, Barrett’s esophagus, and, in severe cases, strictures.

Key risk factors include obesity, hiatal hernia, smoking, and certain medications (e.g., calcium channel blockers). The condition affects roughly 20% of adults in the United Kingdom, and many remain undiagnosed because the classic heartburn sensation can be mild or absent.

How Epigastric Pain and GERD Overlap

When acid reflux reaches the upper stomach, the resulting irritation can radiate upward into the epigastric zone. This “reflux‑related epigastric pain” often mimics ulcer pain but lacks the classic nocturnal worsening seen with peptic ulcers.

Typical patterns:

- Post‑prandial rise: Pain intensifies 30‑60 minutes after a large or fatty meal.

- Positional effect: Bending over or lying flat worsens the ache.

- Associated symptoms: Bitter taste, belching, or a sensation of a lump in the throat.

If you notice these clues, a GERD work‑up is usually the next step.

Diagnosing the Connection

Doctors start with a detailed history and physical exam. The next steps often involve objective testing to confirm reflux and rule out other causes.

| Test | What It Measures | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Endoscopy | Visual inspection of esophagus, stomach, duodenum; biopsies for Barrett’s or H. pylori | Direct visualization, can treat ulcers or strictures during the same procedure | Invasive, requires sedation, higher cost |

| 24‑hour pH Monitoring | Acid exposure time in the esophagus over a full day | Gold standard for confirming reflux, quantifies severity | Discomfort from catheter, may miss intermittent reflux |

| Barium Swallow (Upper GI series) | Radiographic outline of esophagus and stomach | Non‑invasive, useful for detecting hiatal hernia | Less sensitive for subtle reflux, radiation exposure |

| Symptom Questionnaire (e.g., GERD‑HRQL) | Patient‑reported frequency and severity of symptoms | Quick, cheap, guides further testing | Subjective, can be influenced by recall bias |

Most clinicians begin with a questionnaire and trial of acid‑suppressing medication. If symptoms persist, they move to endoscopy or pH monitoring to rule out complications such as Barrett’s esophagus.

Treatment Options

Therapy combines lifestyle tweaks, medication, and, when necessary, surgery.

Lifestyle Modifications

These changes address the root triggers of reflux:

- Weight Management: Even a 5‑% weight loss can reduce LES pressure.

- Dietary Adjustments: Cut back on fatty foods, chocolate, caffeine, citrus, and carbonated drinks.

- Meal Timing: Eat at least 3hours before bedtime.

- Head‑of‑Bed Elevation: Raising the mattress 6‑8inches reduces nighttime reflux.

- Avoid Smoking & Alcohol: Both relax the LES.

Medication

First‑line drugs are Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) such as omeprazole or lansoprazole. They block the final step of acid production, providing up to 90% symptom relief.

Typical regimen: 20mg once daily for 4‑8 weeks. If symptoms recur after stopping, a low‑dose maintenance (10mg) may be prescribed.

Second‑line agents include H2‑blockers (e.g., ranitidine) and antacids for breakthrough pain. For patients with delayed gastric emptying, pro‑kinetics like metoclopramide can help.

Long‑term PPI use has been linked to magnesium deficiency, increased infection risk, and bone fractures. Annual labs and a periodic “drug holiday” are advisable under medical supervision.

Surgical Interventions

When medication fails or complications arise, surgeons consider a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. The procedure wraps the upper stomach around the LES, reinforcing the barrier against reflux.

Success rates hover around 85% for symptom control, with a low complication profile (<2% serious adverse events). Candidates are typically those with confirmed acid exposure on pH testing and a hiatal hernia larger than 2cm.

When to Seek Medical Help

If you notice any of the following, book an appointment promptly:

- Chest pain that mimics a heart attack

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) or sensation of food sticking

- Unexplained weight loss or anemia

- Persistent vomiting or black, tarry stools

- Sudden worsening of pain despite over‑the‑counter remedies

Early evaluation prevents progression to Barrett’s esophagus, strictures, or even esophageal cancer.

Common Pitfalls & Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ

Can epigastric pain be caused by something other than GERD?

Yes. Gastric ulcers, pancreatitis, gallstones, and H. pylori infection are common alternatives. A thorough work‑up is needed to exclude these before labeling the pain as reflux‑related.

How long should I stay on a PPI before evaluating effectiveness?

Most guidelines suggest an 8‑week trial. If symptoms improve, a taper or maintenance dose can be discussed. Lack of improvement after this period warrants further testing.

Is surgery a cure for GERD‑related epigastric pain?

Surgery dramatically reduces acid exposure in most patients, but it’s not a guarantee. Lifestyle habits still matter, and a small percentage may need medication after the procedure.

What role does a hiatal hernia play in my symptoms?

A hiatal hernia allows the stomach to slide up through the diaphragm, weakening the LES. Even a small (type I) hernia can amplify reflux and thus epigastric pain.

Can over‑the‑counter antacids replace prescription medication?

Antacids provide quick, short‑term relief but don’t address acid production. They’re fine for occasional heartburn, but chronic epigastric pain will usually need a PPI or H2‑blocker.

Understanding the link between epigastric pain and GERD empowers you to seek the right tests and treatments. With the right mix of lifestyle changes, medication, and, if needed, surgery, most people find lasting relief.

Winston Bar

October 17, 2025 AT 16:00Another post about reflux, yawn.

genevieve gaudet

October 18, 2025 AT 16:31It's interesting how the epigastric region acts like a crossroads for all our digestive woes. I keep thinking about how ancient healers might've described this "central fire" without any gadgets. The modern breakdown of symptoms feels almost poetic when you consider the body as a whole. Anyway, cut the fat and stop lying down after meals, simple as that.

Patricia Echegaray

October 19, 2025 AT 17:02What they never tell you is that the pharma giants are busy pushing PPIs like they're candy, while the real culprits are the hidden electromagnetic waves from 5G towers messing with our LES. Obvious? Not to the average joe, but the data is out there if you look past the mainstream narrative. The government knows, the corporations profit, and the rest of us just swallow pills.

Miriam Rahel

October 20, 2025 AT 17:33When approaching a patient with epigastric discomfort, the initial step is a comprehensive history taking that elucidates the temporal relationship between meals and symptom onset.

Subsequently, a validated symptom questionnaire such as the GERD‑HRQL should be administered to quantify severity.

Physical examination must focus on abdominal tenderness, guarding, and signs of chronic liver disease.

Laboratory assessments, including a complete blood count and serum electrolytes, are useful to rule out anemia and metabolic disturbances.

Upper endoscopy is indicated when alarm features like dysphagia, bleeding, or weight loss are present, allowing direct visualization and biopsy for Barrett’s or H. pylori.

For patients lacking alarm signs, an empiric trial of a proton pump inhibitor for 8 weeks remains a cost‑effective diagnostic maneuver.

If symptoms persist after therapy, ambulatory 24‑hour pH monitoring provides the gold‑standard measurement of esophageal acid exposure.

Impedance‑pH studies add the benefit of detecting non‑acid reflux episodes, which may explain refractory cases.

Barium swallow remains valuable for identifying structural abnormalities such as hiatal hernia or strictures before endoscopy.

In cases where motility disorders are suspected, high‑resolution esophageal manometry should be performed to assess LES pressure and coordination.

All diagnostic modalities must be interpreted in the context of the patient’s comorbidities, medication profile, and lifestyle factors.

Weight reduction of even 5 % of body mass has been shown to improve LES function and reduce reflux episodes.

Elevating the head of the bed by 6–8 inches mitigates nocturnal reflux by utilizing gravity.

Patients should avoid known triggers, including tobacco, alcohol, and foods high in fat, caffeine, and acidity.

Long‑term PPI use warrants periodic monitoring of serum magnesium, calcium, and bone density to preempt adverse effects.

Finally, surgical referral for laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is appropriate when medical therapy fails and objective testing confirms pathological reflux.

Samantha Oldrid

October 21, 2025 AT 18:04Wow, look at us all following the mainstream medical script. Sure, let’s just pop another pill and call it a day.

Kevin Adams

October 22, 2025 AT 18:35Ah, the ivory tower of gastroenterology! So much gravitas, so little soul-!!! The whole universe of reflux is reduced to a pill box, as if we’re children playing with toy doctors. Yet the patient’s lived experience is a storm of agony that no endoscope can capture!

Katie Henry

October 23, 2025 AT 19:06Indeed, each step we take towards understanding must be matched by compassion and perseverance. Let us rally around those battling chronic pain, encouraging incremental lifestyle changes and vigilant monitoring of therapy. Together, we can transform data into hope.

Joanna Mensch

October 24, 2025 AT 19:36The real reason GERD spikes is hidden surveillance tech interfering with our nervous system. It’s not a coincidence.

RJ Samuel

October 25, 2025 AT 20:07Honestly, blaming unseen signals for every stomach ache is a lazy shortcut. The body works the way it does because of diet, weight, and plain old gravity.

Nickolas Mark Ewald

October 26, 2025 AT 19:38I’ve seen many people find relief by simply adjusting meal times and avoiding late‑night snacks.

Chris Beck

October 27, 2025 AT 20:09That’s cute, but you’re ignoring the fact that most people need medication to survive. Those “simple” fixes rarely work for the majority.

Sara Werb

October 28, 2025 AT 20:40Yo, the whole system is rigged! They push us pills while the real enemy is the secret ingredients in processed food-obviously laced with nanobots! Nobody tells ya about the mind‑control additives that keep us glued to the reflux cycle.

Russell Abelido

October 29, 2025 AT 21:11It’s heartbreaking to see so many suffer under those hidden agendas. 😢 We deserve truth and real solutions, not just another prescription.

Steve Holmes

October 30, 2025 AT 21:41Ultimately, a balanced approach that respects both scientific evidence and individual experience creates the best outcomes for patients.

Tom Green

October 31, 2025 AT 22:12Remember, everyone’s journey with GERD is personal. Seek the guidance of a trusted clinician, stay curious about lifestyle tweaks, and never hesitate to ask for a second opinion if something feels off.