When you're heading to a region where malaria prevention, the steps taken to avoid infection by the malaria parasite, typically through medication, protective gear, and environmental controls. Also known as antimalarial measures, it's not just about taking a pill—it's a full system of protection that saves lives. Malaria isn't just a tropical disease you read about. It's a real threat, carried by mosquitoes that bite at dusk and dawn. Every year, millions get infected, and thousands die—most of them children. But here’s the good news: malaria is 100% preventable if you know what to do and do it right.

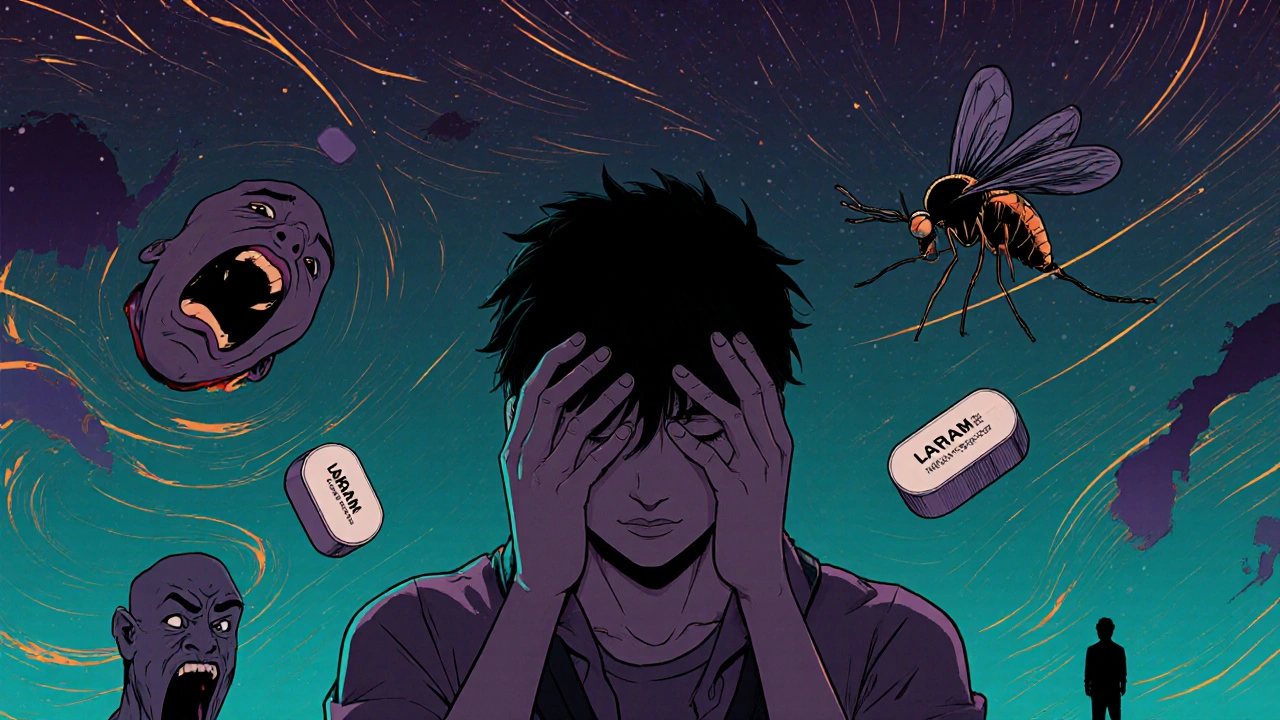

You can’t just rely on one thing. Malaria prevention works like a chain: each link matters. The strongest link is antimalarial drugs, medications taken before, during, and after travel to stop the malaria parasite from developing in the body. Common ones include doxycycline, atovaquone-proguanil, and mefloquine. But not all are right for everyone. Some cause dizziness, others can’t be used if you’re pregnant or have depression. You need to talk to a doctor at least 4–6 weeks before you go. These aren’t over-the-counter snacks—they’re prescription tools with real side effects and timing rules. Then there’s mosquito nets, treated bed nets that create a physical barrier against malaria-carrying mosquitoes while you sleep. These aren’t just any nets—they’re long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), soaked in chemicals that kill or repel mosquitoes on contact. Sleeping under one is the single most effective way to avoid nighttime bites, especially in places with no screens or AC. And don’t forget insect repellent, topical products applied to skin or clothing to deter mosquitoes from landing and biting. DEET, picaridin, and oil of lemon eucalyptus are proven. Spray it on your socks, your sleeves, your neck. Reapply after sweating or swimming. No repellent lasts forever, and mosquitoes will find any exposed skin if you’re careless.

It’s not just about what you take or wear. It’s about when and where you’re active. Avoid being outside between sunset and sunrise. Wear long sleeves and pants—even in the heat. Stay in air-conditioned or screened rooms. Use fans; mosquitoes struggle to fly in strong air currents. If you’re staying in a place with open windows or poor screens, treat your clothes with permethrin. It’s safe, long-lasting, and works on fabric. And if you come back home and get a fever—even weeks later—tell your doctor you were in a malaria zone. Delayed cases happen, and early treatment saves lives.

What you’ll find below isn’t a list of random articles. It’s a collection of real, practical guides that connect directly to how people manage health risks while traveling, using medications safely, and avoiding preventable diseases. From how antimalarial pills interact with other drugs to what to pack in your travel first-aid kit, these posts give you the details you won’t get from a brochure. No fluff. No guesswork. Just what works—and what doesn’t.

Compare Lariam (mefloquine) with safer, more effective alternatives like Malarone and doxycycline for malaria prevention. Learn which drug is best for your destination and health profile.